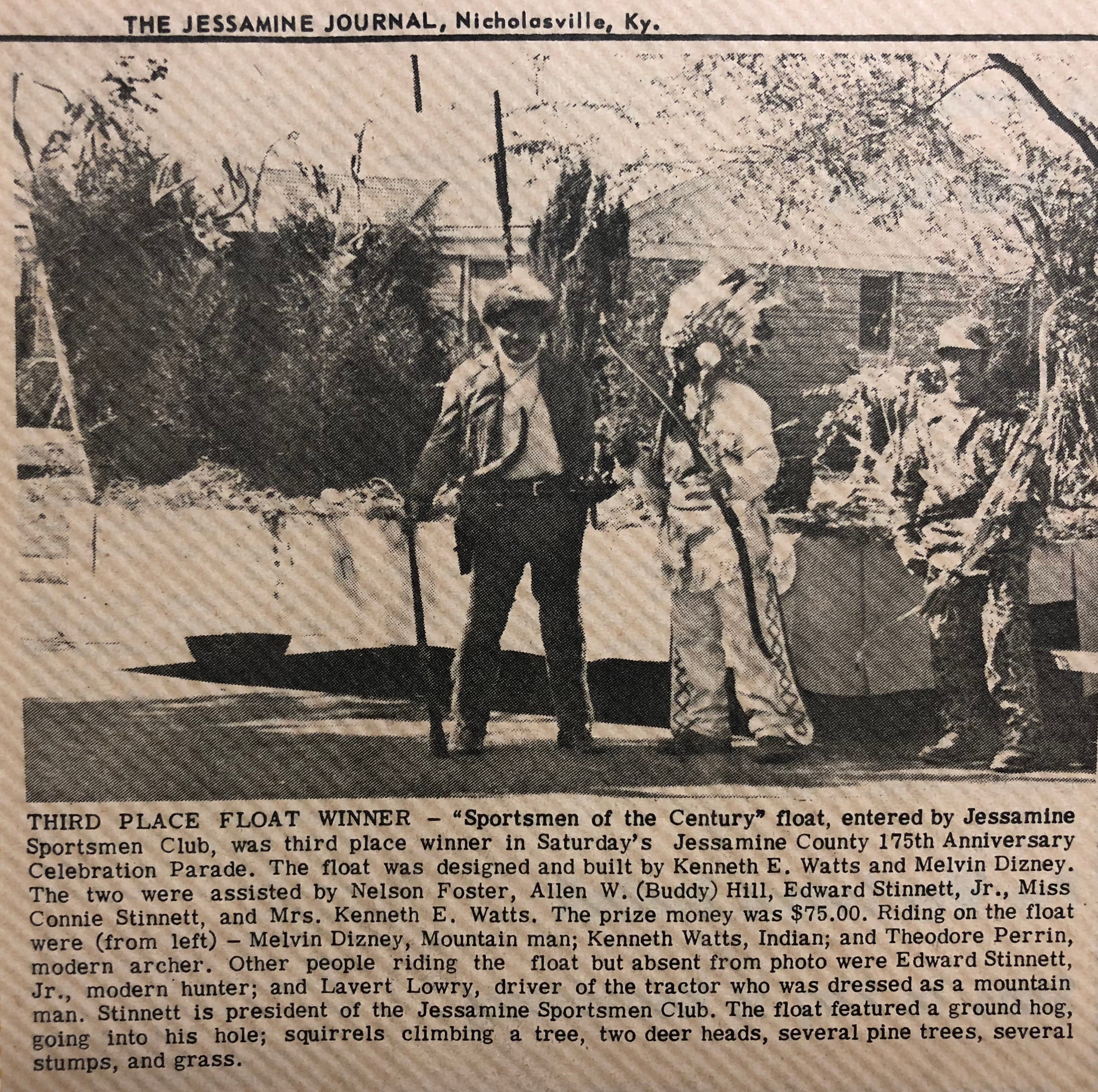

Preserving History

Published 12:40 pm Thursday, June 28, 2018

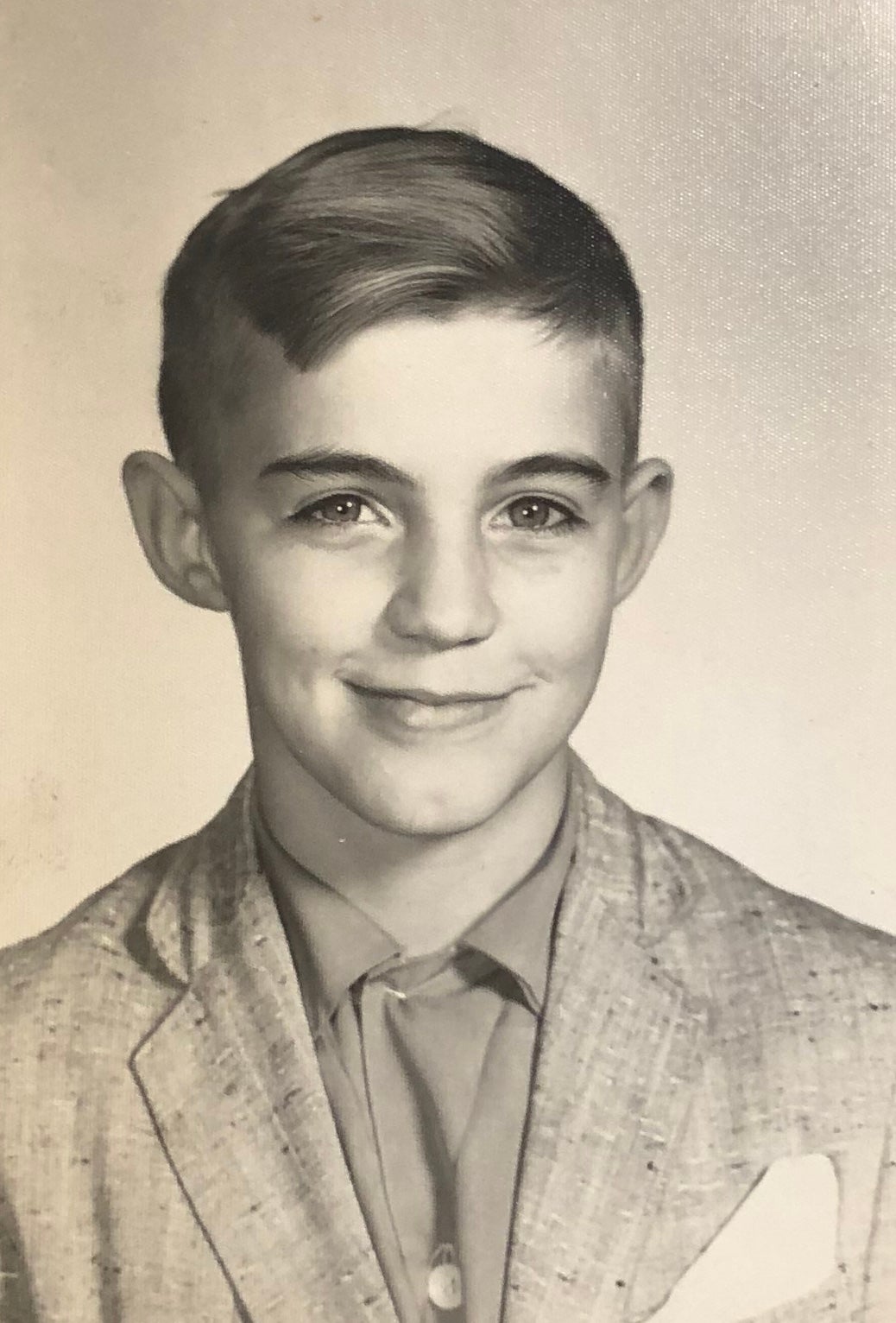

Lifetime resident Kenny Watts remembers ‘good old days’ in Jessamine County

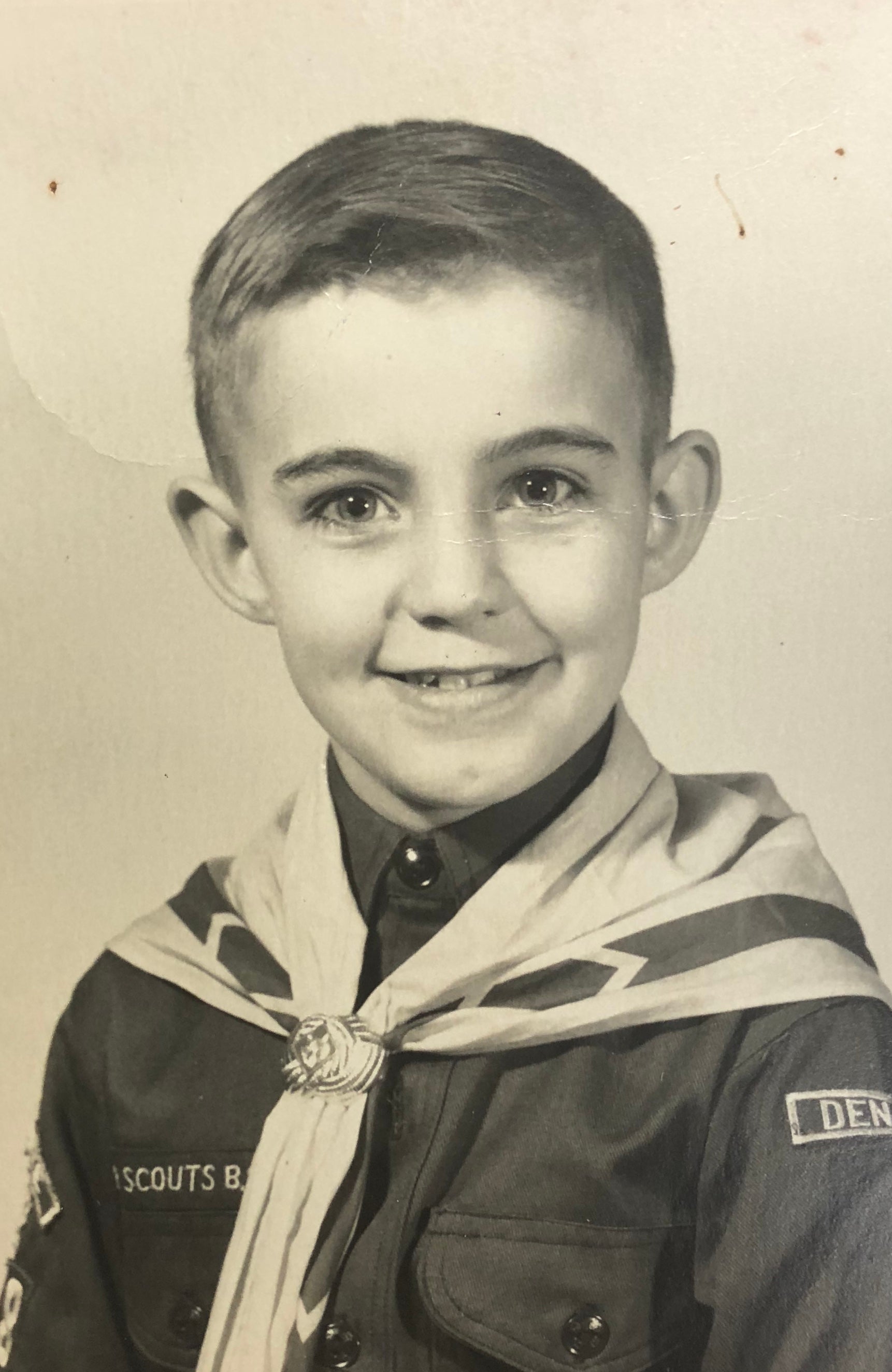

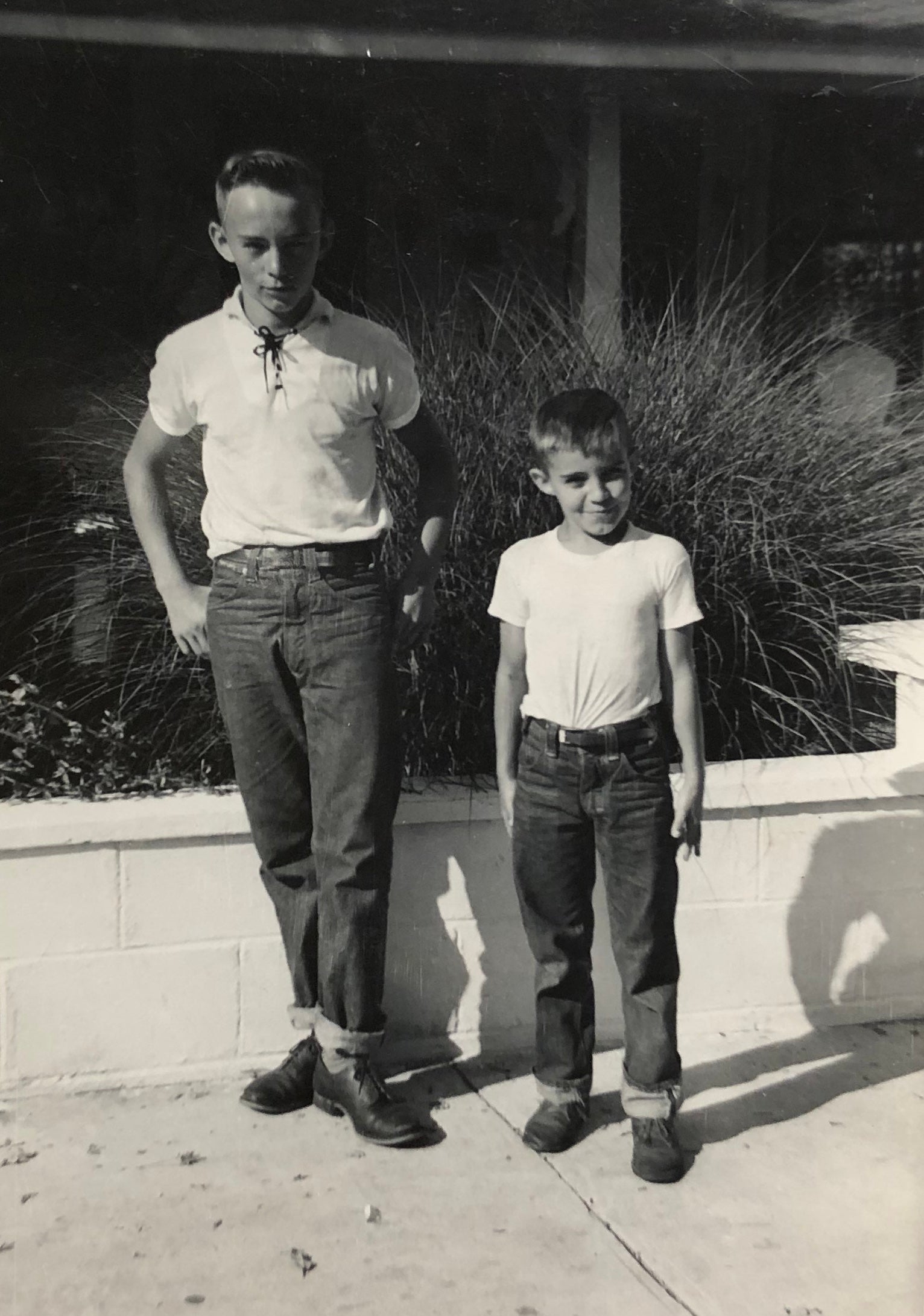

Kenneth Watts was born and raised in

Jessamine County after his family came to

live here by way of the Kentucky River in 1805.

Growing up, Watts was one of nine children and

can remember how different the county was in

stories he was told from before his time and in

the memories he has made throughout his

life here.

“I remember that everyone

knew everyone,” Watts said.

“You didn’t lock your doors

at night. I remember once my

aunt sent me a letter and put

a silver dollar and taped it on

a piece of paper which said,

‘happy birthday, Kenny Watts

Nicholasville KY,’ and they

delivered it to me. The mailman

even knew all the kids’

names. How impressive is that

it (the county) was so small

he even knew what house to

bring it to, and no one stole

the money out of it.”

Watts said his family came

to Kentucky from Virginia

by boat which they would

sometimes have to pull along

through the Kentucky River

when the water was too shallow. Happening

upon what is now known as Camp Nelson,

his family was tired of traveling and decided

to stop in what later became known as Jessamine

County.

“They were looking for a place to stay and

said, ‘why don’t we just stay here? We have

been traveling all this time,’ and the rest is

history,” Watts said.

His grandfather opened a general store in

what is now the Democratic headquarters

on Main Street. His father worked for the

old T.C. Willis Grocers, a building which is

currently undergoing renovations.

“We were told that this street (Main

Street) was a buffalo trail,” Watts said. “The

Journal was where the old county jail was

located on Main Street and they had written

it took two weeks for the herd to pass night

and day as they traveled to Great Crossing

and Stamping Ground. That was some buffalo

herd.”

Growing up, Watts was told stories of how

his uncle at 5 years old would wait by where

the current Central Bank sits for tobacco

farmers to come along with their horses

pulling wagon loads of tobacco. Watts said

the farmers’ wagons would become stuck in

the mud of the flowing creek and all the kids

would get behind the wagon and push it up

the muddy hill.

“Sometimes, they would have to unload

the tobacco and then carry it up the hill and

they would pay those boys a nickel,” Watts

said. “They would have the tobacco sticks

and they would carry them back up the hill

to reload. They would take enough off for

the horses to be able to get up there and they

would sit down and wait for the next wagon

to come through so they would get another

nickel.”

Watts worked at the old L & M grocery

store on Saturdays when he was a teenager.

One Saturday in particular, Porter Wagoner

came in, and being a 16-year-old boy behind

the counter, Watts was quick to recognize

him and let him know it.

“I said ‘I know who you are,’ and he said,

‘OK, well who might you be?’” Watts said.

“I told him I get off at four and he said, ‘well

how about I buy you a Coke.’”

Not long after Watts agreed, Dolly Parton

walked in the store. she was 16 years old,

just like himself, and Watts said he quickly

told her he had seen her singing on television.

“We sat outside and talked for two-tothree

hours,” Watts said. “Porter got ready to

leave. They were going to play the Jessamine

County High School. She asked me what I did, and I told her I played

the guitar and drums. She said, ‘we are down a drummer. Our drummer

is sick and can’t make it. Will you come and play drums for us?’ I said,

‘no, I can’t do that. I am going frog hunting.’”

Sometimes, Watts said a group of 10 to 12 boys would hop the trains

up-town to what is now known as Brannon Crossing. Spending the day

hunting and swimming in the ponds, the group would make sure to

catch the 5 p.m. train coming back down to Danville in order to make

it home for dinner.

“We would be gone all day,” Watts said. “If the train was going slow

we would get on top of the boxcars and take off running and jump and

land in the sand cars. They would call detectives on us, but they were

so fat they couldn’t catch us, and we knew where we were going and

they didn’t, so we would jump the creek and they couldn’t get across

the creek.”

Watts said his mother never turned down any hobo riding the trains

either. Sometimes, Watts and his friends were bribed to try and get the

hobos food, and his mother would pack them a sack full of biscuits,

bread and whatever kind of meat she had on hand.

“After we had fed them and talked they would say get away because a

guy would walk down with a big stick and check cars and look in them,”

Watts said. “They would stand in the back and in the dark. Later they

would wave at us when they would leave and take off.”

Sunday afternoons Watts said were spent washing your car and swimming

at a pond past the Black Ridge Corner Restaurant.

“Everyone would go down there and swim and wash their cars on

Sunday,” Watts said. “You’d bring a bucket and detergent and then your

dad would let you swim after work was done. There were all kinds of

cars that would come down and wash their cars on Sunday.”

Three of Watts’ brothers served in World War II, and Watts was told

stories of how the group went down to enlist with their cousins after th

bombing at Pearl Harbor. Wanting to get even with

the Japanese, Watts said their patriotism would be a

sight to see today because in most areas of the nation

patriotism is going out the door.

“The police called and said, ‘you got to get up here,

your son called from San Diego and is shipping out,’”

Watts said about his parents receiving a phone call in

the 1940s. “They put them (my parents) in a police

cruiser and they ran them to Oak Street where the fire

station was.”

Watts later married and had two children, a daughter

who currently lives in Washington D.C., and a son

who lives in Louisville. Besides a brief time attending

Indiana University, Watts has never

lived outside Jessamine County and

started his own real estate company

in town in 1969, which is known today

as Watts Realtors and Auctioneers,

Inc.

“My mother-in-law said, ‘what on earth do you

think you are doing (going into real estate)?’” Watts

said. “‘You with a wife and two kids and needing

to make a living.’ She said, ‘as soon as you sell your

friends you will be out of business.’ A couple of years

later when we were the biggest ones here she came and

apologized and I told her, ‘well I am just glad I didn’t

have any friends.’”

The small town atmosphere is what still attracts

Watts to Jessamine County after all the years he has

spent here. Walking up and down the street, Watts

said people still stop to speak to you and know who

you are and who your family is.

“When you were a kid they would say, ‘well whose

boy are you?’” Watts said. “I remember if you acted up

on Main Street and the merchants had seen you they

would say, ‘boy, I will call your daddy on you,’ and

that would straighten you right up. Where today they

would probably sue the guy for saying something. That

was how things were. The groups would correct the

kids if they had seen them doing something wrong.”

With all the growth in Jessamine County, Watts said

there are now many people that residents do not know.

Farmland is also becoming scarce, and Watts said his

wish is to see everything preserved.

“I would like to preserve the historical sites so that

the other children can enjoy it,” Watts said. “Just preserve

the history of it.”