Road to freedom led through Camp Nelson for many Black soldiers

Published 4:37 pm Thursday, February 25, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Frederick Douglass, our most famous abolitionist, wrote at the beginning of the Civil War that once a Black man gets a brass “U.S.” on his uniform and a musket on his shoulder, “there is no power on earth that can deny he has earned the right to citizenship.”

African-Americans who escaped slavery later were allowed to serve in the U.S. Army and so earned their emancipation. Those who have seen the 1989 film “Glory” know what an important contribution those Black soldiers made in that great struggle for freedom.

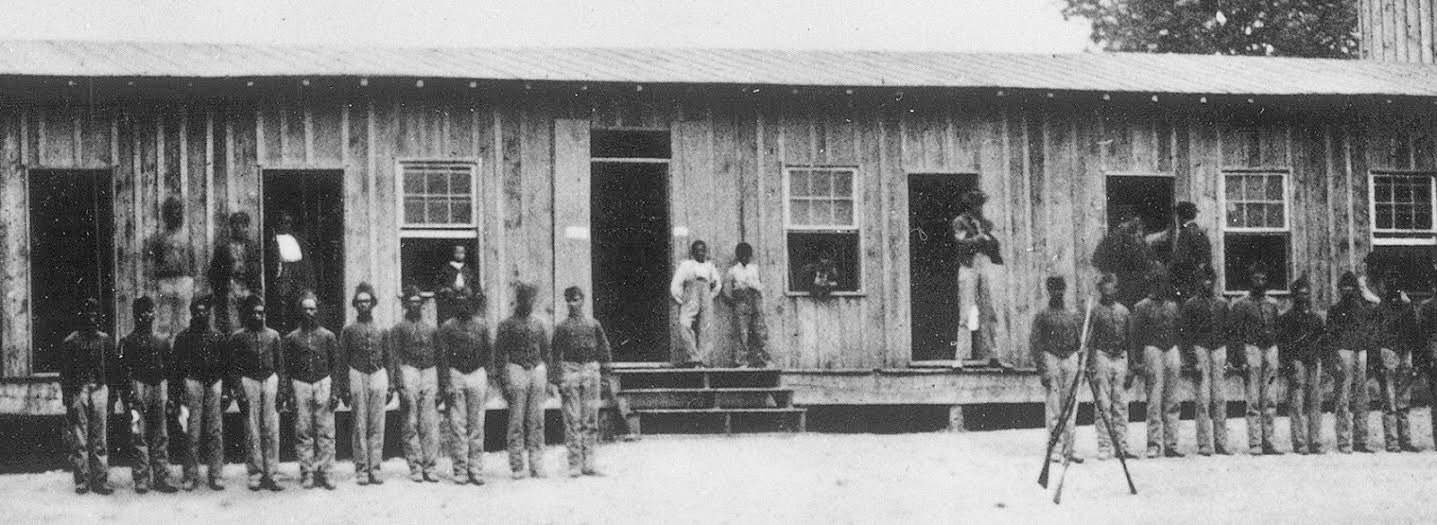

In Jessamine County, Camp Nelson was an important way station on the road to emancipation. The Union supply depot was the third largest recruiting camp for the soldiers who were called U.S.Colored Troops.

It is now the site of the National Park Service’s Camp Nelson National Monument and Camp Nelson National Cemetery.

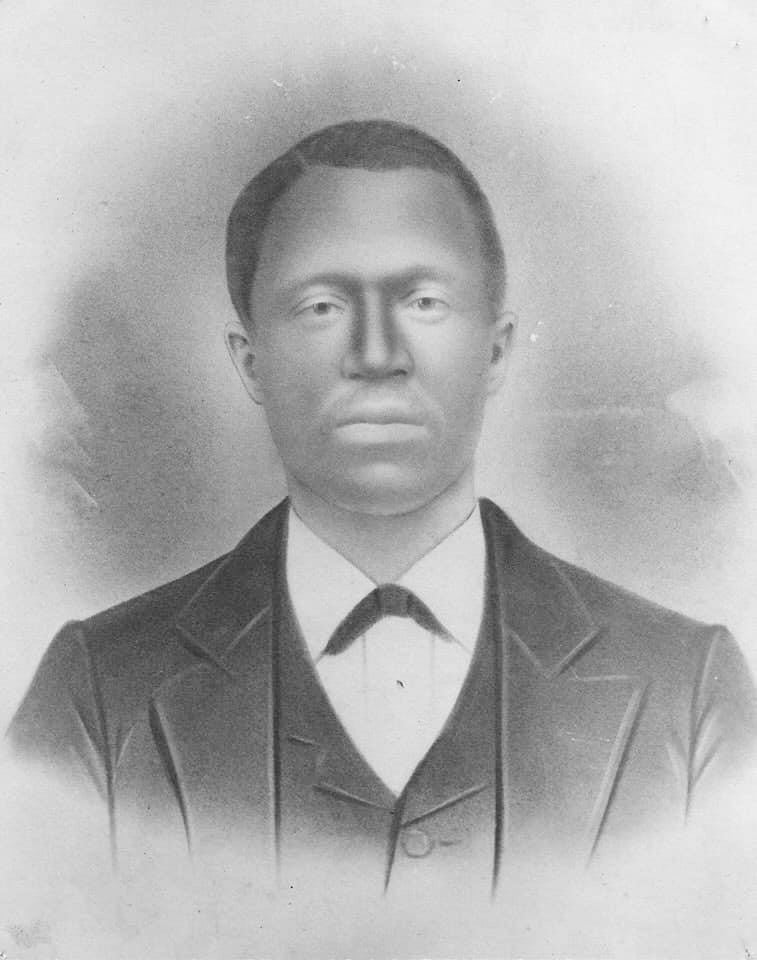

A 25-minute Black History Month video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVYIIOiZnb4) made by the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation’s deTour series tells of the significance of Camp Nelson to African-American history and features an interview with the Rev. Robert P. Gates Sr. of Keene, pastor of the historic First Baptist Church of Camp Nelson and a descendant of Sgt. Jesse Commasel Tull, who was both a soldier and a pastor for the Black refugee community for the families of the soldiers in the area now known as Hall, across U.S. 27 from the park.

In the video, Gates stands in front of the historic Fee Memorial Church, established by the abolitionist minister the Rev. John G. Fee, and tells about those who settled there in the 1860s.

“They came to Camp Nelson because it was said that if you came as a slave, you would get freedom,” Gates said.

Gates explained that President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 was a military order that pertained only to slaves in the Confederate states, not to Kentucky and other slave states that remained part of the Union. For them, serving in the U.S. Army was a way to earn their freedom.

But their families, who lived in the nearby refugee community, were not free.

In November 1864, Gates said, a general at Camp Nelson decided that the refugee community was overcrowed and families were an inconvenience, so 400 people were turned out into the cold. More than 100 of the homeless people died of exposure.

“They were thrown out into the wilderness, and they froze to death,” Gates said.

The story of Camp Nelson is “a story of emancipation and broken promises,” said Ernie Price, superintendent of Camp Nelson National Monument, who also narrates part of the video. “It’s as complicated as Kentucky and the Civil War itself.”

Later, some of the families returned and lived in the community, and “some even live there to this day,” Price said.

The community, known as the Home for Colored Refugees, included a school, Ariel Academy, a post office, a hospital, a cemetery and churches.

In 1866, after the war was over, the U.S. Colored Troops were dispersed to other locations around the country, and Camp Nelson was dismantled and returned to farmland. The only buildings remaining are the Oliver Perry House, or “White House,” which was the officers’ quarters, and the Fee Memorial Church across the road.

Gates said his great-grandfather, Tull, was discharged in Louisville in 1866 and returned to Jessamine County, where several generations of his family have made their home.

The church Gates pastors today is not the original building, but it is on the site of the first Black church at Camp Nelson. Gates said the building that was there before was burned to the ground in 1968. Rumor has it that it was burned by “night riders” because, according to “oral history that was told to me,” there was a Ku Klux Klan leader who lived nearby, Gates said.

For Gates, who is 58, the era of segregation and white supremacist racism isn’t just something he has read or heard about; he’s lived it. He said he remembers, as a young man in the 1970s, going with his brothers to witness a KKK rally on a farm near Nicholasville where there was a cross burning because they were curious, but when they saw it, they turned around and drove away.

Gates prefers to reflect, not on such memories, but on the progress his people have made and the legacy he is working to preserve.

“I’m trying to recreate history,” he said, so that when he is gone, his children and grandchildren can see “the part we played” in the story of Jessamine County, Kentucky and the Civil War.

He is especially proud of his great-grandfather, who organized what is now First Baptist Church of Camp Nelson and also Cedar Top Baptist Church in Wilmore, and he is pleased to follow in his footsteps as a preacher, just as his three brothers followed in his footsteps as soldiers in the U.S. Army.

“It’s part of our heritage, and I want everybody to know the contributions he made as part of the U.S. Colored Troops, because if he never came to Kentucky … my lineage would not have come through Camp Nelson. So I am very proud,” Gates said.

Below are links to the Blue Grass Trust’s deTours video:

https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7w6m33528c

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/a998ea07070543e6a7acda28a219bd4e?fbclid=IwAR3-cHdDj

0fogTqtQALFy-5ZMH2cwqmT7FBjtfHaeq1yoeAb7FDKNQh2pT8