Jessamine County Athletic Achievement Award: Honoring Elmer Stephenson

Published 9:17 am Thursday, October 6, 2016

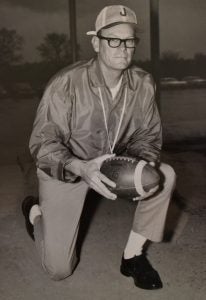

- Photo by Joshua Huff

Some knew him as Elmer Stephenson, but for most, he was simply, “Coach.”

He was a man among men who possessed a gentle touch and firm grip. He was full of “O’ My’s” and a deep understanding of how to thread the line between disciplinarian and mentor.

He was then, and will forever be, a lasting memory within Jessamine County.

When you step onto the fields of East and West Jessamine High, his presence embraces; when either an East or West Jessamine sports team wins, their victory is his legacy.

That was his gift to us.

And this is our gift to him.

On Oct. 21, during halftime of the East vs. West Jessamine football game, Coach will be awarded the Jessamine County Athletic Achievement Award. The award is an opportunity for the county to recognize, preserve and promote the heritage of interscholastic athletics. The award honors contributions and highlights accomplishments of individuals who are worthy of recognition as examples for others to emulate.

It would be foolish to assume that most residents of Nicholasville aren’t already wellversed in Coach’s life. But for those who aren’t, he was a man of many hats. First and foremost, he was a husband and a father; he was a friend, a mentor, a bus driver, an inspector, a social studies and physical education teacher, a lifeguard, an umpire and a painter; he was a veteran of World War II — but for most, he was Coach.

Photo Submitted

He was a man who once berated a future mayor during halftime of a Nicholasville High basketball game while covered, head-to-toe, in talcum powder.

What a story that was.

“Corman!” Coach yelled to a young Sam Corman, the future mayor of Nicholasville, as the team sat in the locker room. “I have been up to my rear end in water with people shooting at me, but I’ve never been as mad at anybody as I am mad at you right now.”

The reason?

Corman tried to glitz up a routine layup just prior to halftime, and missed. As a result, Corman learned a valuable lesson that night: just lay the ball in; Coach learned a lesson that night as well: kicking boxes full of foot powder was not effective in making a statement.

The message may not have gotten through to most of the team, as Brad Stephenson, Coach’s son, recalled the late Pete Royse, former longtime school administrator and former player for Coach, saying that the players tried their hardest to stifle their laughs as Coach stood in front them, madder than sin and covered in powder.

Coach was a man who, prior to baseball games in Somerset, would tell his players to bring fishing poles. Because, why not.

It was simpler times.

He was a man who received anonymous threats because he had the audacity to allow black students the opportunity to tryout for football when the schools integrated in the mid-1960’s.

He was a man who left a lasting impact upon those who were blessed enough to be within his presence.

Just after his death in 1997, Brad recalled receiving a phone call from someone who identified himself as an attorney from Frankfort.

“I just heard through the grapevine that Elmer had died,” the attorney said. “I’m sorry that I didn’t hear in time to pay my respects at the funeral home.”

The reason he called, Brad said, was to thank Coach.

“You’ve never met me,” the attorney continued. “But in 1953, I was playing Little League baseball in Lexington, and I was 12 years old. There was a coach who was trying to intimidate me from the other team. I was pitching and this coach was hollering at me and so forth and so on. Elmer was umpiring behind home plate and finally he had enough. He came out from behind home plate and told that coach to (stop), and leave me alone or he was going to get the park police to escort him out of the park. He came up to me, and just between the two of us, looked at me one-on-one as a 12-year-old kid and he said, ‘Son, don’t ever let anybody intimidate you.’”

The attorney had never forgotten that moment.

Brad recalls a summer day when his father was painting the old Nicholasvile Elementary School building. Brad, just a boy at the time, was bouncing his ball through the hallways when he hit and broke a light fixture.

He knew trouble was brewing.

“He was a disciplinarian for sure,” he said of Coach. “He didn’t let you get away with it.”

Brad went down to the next floor, where Coach was working, and said, “Daddy, I have something to tell you.”

“What’s that son?”

“I was throwing that ball around upstairs, hit a light and broke it. There it is.”

Coach didn’t say anything.

“I thought he was going to spank me or something,” Brad said. “I looked at him and asked him if he was going to spank me. He said, ‘No son. You told me the truth, and you made a mistake. Everybody makes mistakes and you owned up to it. I can’t ask more of you than that.’”

That was Coach, through and through.

Photo Submitted

This was the same man who would spend his Saturdays washing the dirty uniforms of his football team; the same man who, despite no pay, took it upon himself to start a baseball team at Nicholasville High in the early 1950’s.

At first, the team had no uniforms and no money. So Coach turned to his brother, Harry Stephenson, who was the head baseball coach at Transylvania at the time, for help.

Harry ended up selling his team’s old baseball jerseys to his brother for $1 a piece.

The team painted quite the picture in their new uniforms: They looked like a ragtag, band of misfits with a large crimson “T” emblazoned on the uniform. Nicholasville’s colors were purple and gold at the time; Transylvania’s was crimson and white.

But Nicholasville had a baseball team.

That team went to the district tournament in Lexington against Lafayette during that inaugural season. Nicholasville never got to bat in the game, however. Lafayette scored 25 runs in the top of the first inning.

Nicholasville forfeited.

In 1969, the next-to-last year before Coach retired, he took Nicholasville to the state tournament semifinals. And at the same field where he first forfeited, he returned as state championship contenders.

Nicholasville would eventually lose to Owensboro.

“He started the team from nothing,” Brad said. “And before his career ended, he ended up with that kind of result.”

It was no surprise that Coach was named the 1967 CKC Coach of the Year a few years prior to that state tournament run.

“He loved all the kids and they all loved him,” Doris Stephenson, Coach’s wife said. “He just loved teaching and helping young people. He was born as an athlete and always was.”

That was the trick up his sleeve: A love for the game and his players. It was a love that spanned decades, and it was that love that earned him the Jessamine County Athletic Achievement Award.

It’s an award that would have thrilled coach, Brad said.

Doris agreed.

He probably would’ve simply uttered, “O’ My,” she said.

“The greatest compliment that you can give somebody that was a teacher and a coach, was the fact that their life was impacted,” Brad said. “It’s my guess, based on the people that I’ve known and the number of grown men that I saw weep at his funeral in 1997, I think that would be a summary of his life that he was a person who had other people’s best interests in mind and he tried to exhibit character in his relationships.”